The chronotype is not learned, but follows a genetic predisposition. As a result, we cannot choose whether we are early or late types.

I am therefore often asked whether the chronotype can be changed over the course of life or by certain external factors. My answer is: Yes and no! The basic chronotype does not change. Anyone who is an early type does not become a late type and vice versa. In one of our projects alone, there was a gap of 13.5 hours between the earliest early type and the latest late type. The following factors influence the chronotype:

Your chronotype depends on the comparison group

Strictly speaking, the chronotype classification itself is not based on a natural classification scheme, but on the basis of simple, man-made statistics.

Example:

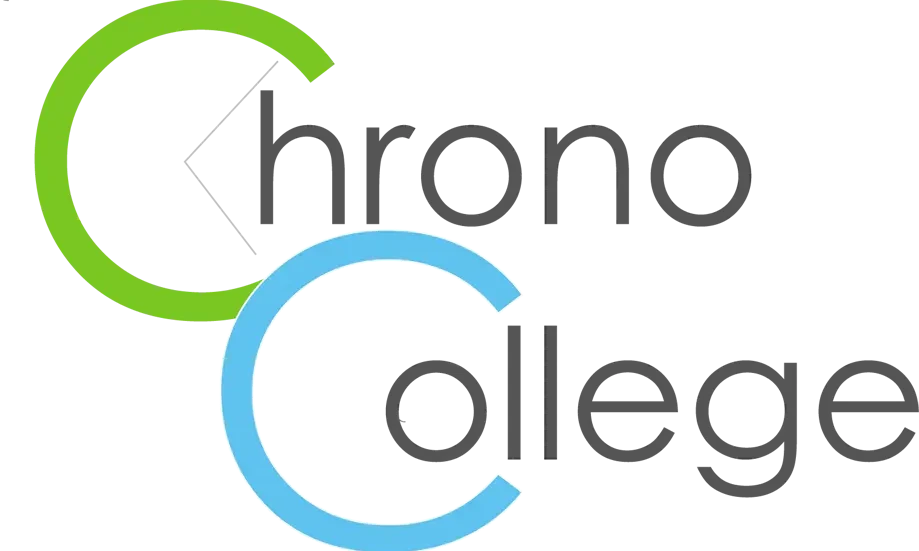

According to the current distribution scheme of chronotypes among the German population, a mild late type goes to bed around 12:30 a.m. The proportion of participants. where this was determined as the time to fall asleep is around 12.5% in the current statistics, compared to almost 16% where a natural time to fall asleep of around 12:00 a.m. was determined. The designation “normal type” is not based on a genetic assessment, but describes the largest group within the overall distribution. If the proportion were reversed, with 12.5% going to bed at 12:00 a.m. and 16% at 12:30 a.m., then the latter would be counted among the normal types and the former among the slightly early types.

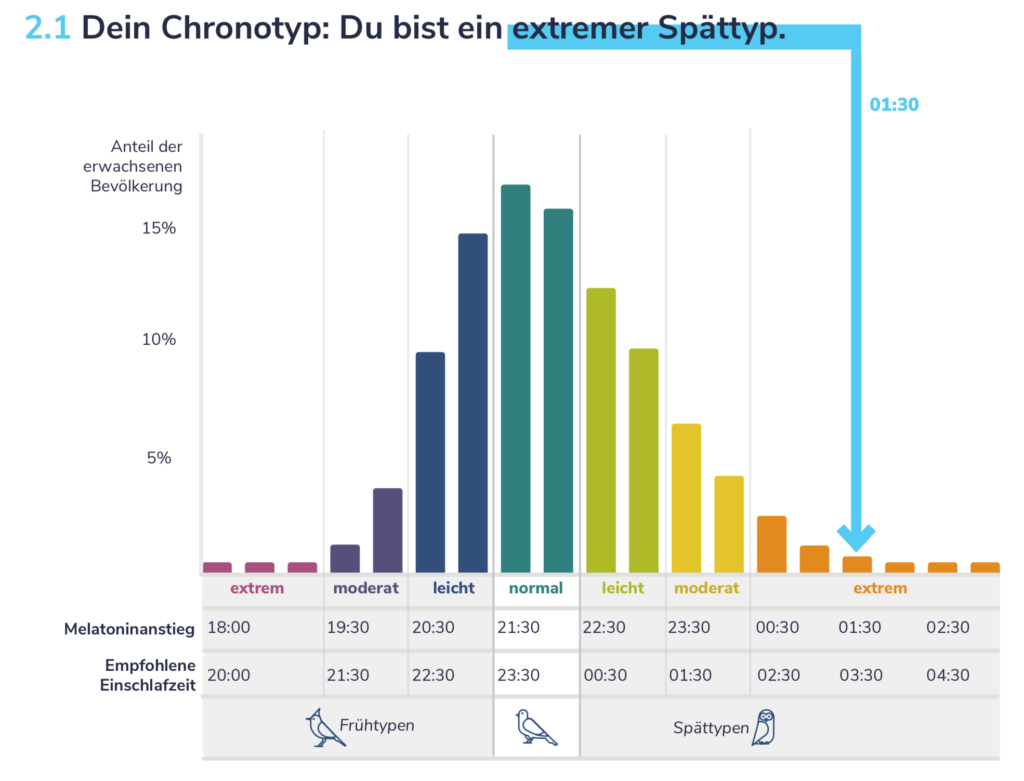

The figure shows the chronotype distribution based on a survey in the USA. Blue is the group of people between the ages of 20 and 24, red is the group between the ages of 70 and 74. If you only look at the group of seniors, then the normal type is about 30-45 minutes later than in the group of young people.

In the end, early, normal and late are just as relative as big, normal and small. The classification is always to be seen in relation to the group of those with whom one is compared. It is therefore possible that, compared to the inhabitants of Berlin, one is one of the early types, and in the Bavarian Forest one of the normal types. A comparison with another country can also lead to a different chronotype for you.

The total German population is currently classified on the basis of a survey that has been running for more than 20 years using a questionnaire (MCTQ) from the LMU Munich. All current chronotype distribution graphs are based on this survey. With the new RNA chronotype test from BodyClock, the group of those who have a corresponding test result is growing. It remains to be seen how the distribution in the population will change if necessary.

However, the starting point for the classification is always an individual factor that is independent of others, such as the DLMO(RNA chronotype test) or the mid-sleep (MCTQ questionnaire). The chronotype is only a guide for further measures in the private or corporate sector, you should work with the constant factors such as DLMO or mid-sleep.

Does daylight saving time change the chronotype?

Another question I often get asked in interviews is whether or not the chronotype adjusts to daylight saving time.

Again, the answer is “yes and no”.

Eine aktuelle Studie hat gezeigt, dass sich der DLMO im Sommer durchschnittlich um 1h nach vorne verschiebt. This may now appeal to all daylight saving time advocates. However, the whole thing has a catch. Because it is not summer time that triggers this shift, but the course of the sun in summer itself. Because the inner clock or the DLMO doesn’t care how we measure our time. This means that the internal clock shifts by 1 hour from one solstice to the next, and is not caused by the time change.

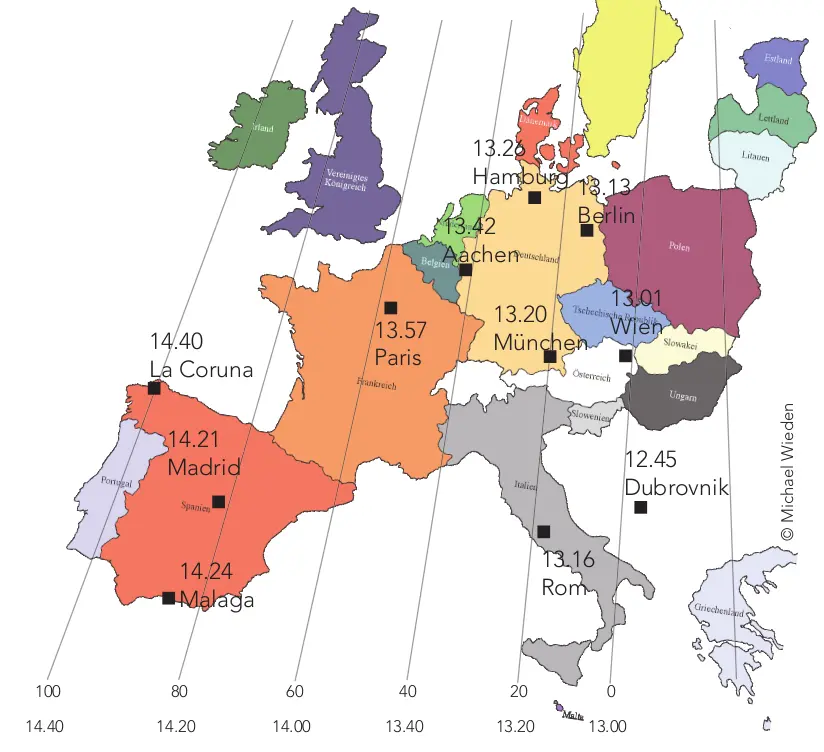

On the other hand, the result is just an average consideration. There are people for whom inner clock shifts even more extreme and others for whom it doesn’t shift at all. The most important point, however, is alignment with the sun. For the internal clock, “noon” is always the zenith of the sun. This means that regardless of summer or standard time, the zenith of the sun never shifts. However, the course of the sun is a central element for adjusting the internal clock.

As an extreme example:

In the extreme west of Spain, the sun is at its zenith at 2:40 p.m. on the summer solstice. So while people there are often close to knocking off time in summer, it is still “midday” for the body. The processes in the body are therefore still in contradiction to the processes in society.

Strictly speaking, however, the chronotype itself does not change at all as a result of daylight saving time, since the average of the shift across all people is calculated (see explanation for comparison group). Only the DLMO is shifting to varying degrees. Our inner clock does not adjust itself to DST either, so there is no evolutionary high-speed development. There is only a small window of time around the summer solstice when it may have no or reduced negative effects for a certain proportion of people. However, the problem will become more acute when summer time becomes normal time, i.e. remains in place all year round. Because in autumn, winter and spring the average temporary summer effect does not exist, and most of them now have to live even more extreme against their inner clock over a long period of time.

And for all those who bring the argument “habituation” into the field, this article is recommended.

https://www.wieden.com/chronobiologie-news/gewoehnung-ein-fataler-trugschluss/

Does chronotype change with age?

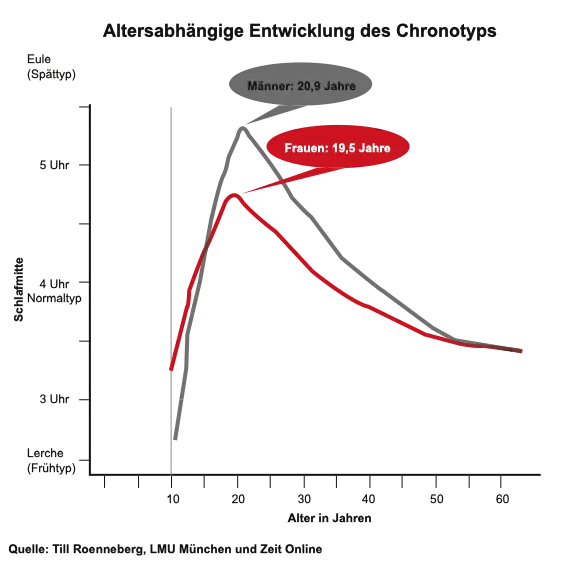

The third possibility of shifting the chronotype is age-related. However, it also applies here that the chronotype does not change fundamentally. Babies sleep up to 16 hours a day from birth. This gradually decreases until puberty. From this point on, the natural need for sleep perpetuates to an average of 8 hours. Until then, there’s no point trying to identify a chronotype. With puberty, however, the biological time to fall asleep begins to be pushed back (later). From the beginning of puberty to adolescence (peak in women 1 year earlier than in men), this shifts by up to 2.5 hours, so that in the age peak (in men approx. 20.5 years, in women approx. 19.5 years) the average mid-sleep for men is around 5:30 a.m. and for women at 4:30 a.m.

This is exactly the reason why it makes no sense to try to force young people to go to bed earlier. That would be like trying to put young people in their children’s shoes. The genes have driven a development here that cannot be stopped or reversed. It is only from adolescence that we slowly start to get younger again, until we reach the point of puberty again at around 60. Here, too, it should be noted that adolescents only appear to change their chronotypes. Because this only happens in comparison with all age groups. If you only compare the age group between 12 and 20 years, many late types would be more normal types.

Will the chronotype ultimately change?

The individually natural point in time of your increasing melatonin secretion (DLMO) is the starting point. This is determined most precisely via an RNA test. The classification into a chronotype is then based on this, as well as taking into account the comparison group.

It is important to note that chronotype per se is not a genetic trait, but follows a genetic predisposition (in this case, DLMO) in its classification. It’s like shoe size. This is not a genetic trait, just a man-made unit of measure that follows a genetic predisposition (the length of the foot). So, if we wanted to be scientifically exact, we would always have to look at the fundamental base unit first (length of the foot or DLMO). The chronotype is merely an indication of a range within a group-specific distribution pattern.

Michael Wieden beschäftigt sich als Betriebswirt seit 2002 mit der Chronobiologie im Personalmanagement. Schon 2003 hielt er hierzu seinen ersten Vortrag auf einer Veranstaltung der INQA (Initiative der neuen Arbeit).

Zu den Themen „Chronobiologie im Personalmanagenement“ sowie mobilen Arbeitsformen hat er bereits Bücher geschrieben, und dabei den Begriff „Liquid Work®“ geprägt.

Zusammen mit Claudia Garrido Luque gründete er 2014 die aliamos GmbH und berät seit dem Kommunen, Unternehmen und Kliniken zum Betrieblichen Gesundheitsmanagement. Von 2012 bis Ende 2016 war er externer Wirtschaftsförderer für die Stadt Bad Kissingen und Initiator des weltweit einzigartigen Projektes „ChronoCity – Pilotstadt Chronobiologie“. Zu ChronoCity®, Chronobiologie-Themen und mobilen Arbeitsformen trat er wiederholt als Experte in verschiedenen Fernsehformaten (z.B. TerraX, Planet Wissen, W wie Wissen, Xenius etc.) auf. Zudem war er von 2014 bis 2017 Mitglied des Arbeitskreises „Zeitgerechte Stadt“ der ARL – Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung in Hannover.

Aktuell hält er Vorträge zum Thema “Chronobiologie im Personalmanagement” und “Mobile Arbeitsformen”, und berät Unternehmen bei der Umsetzung chronobiologischer Ansätze in Unternehmen und Kliniken.